Above: Exhibit 3226A – Tamerlan Tsarnaev (left) with friends Viskhan Vakhabov (center) and Abubakr Turshaev (right), circa 2008-2011. Over the last three years, I’ve discovered information about Vakhabov that calls into question my entire understanding of the Boston Marathon bombing.

Introduction

For awhile now, I have been alluding to the idea that if Dzhokhar Tsarnaev did not conspire to commit the Boston Marathon bombing with his older brother Tamerlan, someone else had to.

We know from the court records that while Tamerlan bought some of the bomb materials, there are several key components not accounted for in either Tamerlan or Dzhokhar’s purchases. This includes the backpack carried by Dzhokhar to the second blast site on Boylston Street, as well as the pressure cooker inside, the large amounts of gunpowder used to construct them, and a plethora of extraneous explosives later recovered after the Watertown shootout.

All this has made me wonder, time and again: were others involved? If so, who are they? Why do they get to walk free while Dzhokhar sits on death row?

I’ve been pursuing these unusual suspects for the better part of three years, even when I didn’t quite realize what I was looking for. During this time, tracing these leads and others, I came to have a fundamentally different understanding of the Marathon bombing than anything publicly written about the case to date. This post and the ones that will follow contain information collected slowly over the last three years, when I was still trying to sort out Dzhokhar’s role in the crimes. These were oddities I could not resolve, and was forced to set them aside for someday.

Finally, it is time to publish them.

I must stress that I don’t have any definitive answers. What I have instead is a series of questions I have not been able to answer, all about three people of interest. This post is about the first one, although they do have one thing in common: they all, at one time, knew Tamerlan Tsarnaev.

Wait, Why Tamerlan?

I know this probably seems like a departure. In doing this project, I have been upfront in caring chiefly about Dzhokhar, not Tamerlan. It was Dzhokhar on trial, Dzhokhar convicted, Dzhokhar sentenced to death when, from the very beginning, I knew something was wrong. In all narratives, it was Dzhokhar’s voice that had been stifled, erased, and shoved under the rug. Over the last three years, I hope I have done an adequate job in presenting him as his own person, to separate his reality from the convenient stories told by those who never cared to know his point of view. In this time, I have come to learn: he is not a person who would want to do any of this, and in fact did little-to-none of it. But at this stage, there isn’t much more I can learn without speaking to him directly. Indeed, there have been many times when members of my own team have commiserated with me, about how much could be cleared up if we could just ask Dzhokhar. But, thanks to the government-imposed Special Administrative Measures, we won’t be able to do that any time soon.

However, this process has not been as forgiving to Tamerlan. In uncovering exculpatory evidence about Dzhokhar, I almost always did so through confirming incriminating evidence about Tamerlan. It has never been my intention to throw Tamerlan under the bus. I merely wanted to get the facts straight and separate two people who, through convenient storytelling, were melded together and held accountable as one. I understand why it was so easy for the government and the media alike to do it. Although tragic, there is something almost romantic about the prevailing narrative of Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev – united against the world, plotting in secret, blood brothers in more ways than one.

But the facts don’t back this up. They were seven years apart in age; Dzhokhar was away at college and open to his friends in his opinion that they didn’t want to deal with Tamerlan. The brothers could not objectively be described as close. Moreover, despite what the prosecutors claimed in opening arguments, there is no evidence Dzhokhar and Tamerlan ever arranged meetings to plan and prepare for the attack. The cell phone evidence is completely devoid of this, even though analysts testified that they recovered the content of Dzhokhar’s cell phones (and, testimony shows, Tamerlan’s own phone was recovered intact).

I have worried about what this all means. That Tamerlan may have kept Dzhokhar as some sort of hostage, or an unwitting instrument, made aware of the horrible truth of his actions only after the fact. That Dzhokhar kept quiet because no one would believe that he – a young Muslim male, so often stereotyped in this country – could have been anything but the most eager of accomplices.

In that regard, history would have proved him right.

Worse, it has become clear that, with the likelihood of unnamed accomplices, Dzhokhar is not only paying for his brother’s sins, but the sins of others. This, I firmly believe, is not justice.

However, in diving into the ins and outs of Dzhokhar’s life, the people he spent time with, his interests and his fears, one thing became clear very fast: no one in his social circles could account for the missing suspects. Friends went to prison for lying to the FBI, throwing away his backpack, or selling drugs – not plotting terrorism. The others, some who came to trial to testify for him, seemed like normal young people in Boston – like college students I’d known and the college student I’d been in the same city, ten or so years earlier. I could find no leads lurking there.

So I had to look back at the lynchpin of the case, the person I hadn’t been able to clear of wrongdoing. This entire case has always hinged upon his brother.

It’s no secret that mysteries still abound about Tamerlan Tsarnaev and his movements in the months and years before the bombing. In a 2017 interview with WBUR, even prosecutor Bill Weinreb admitted there were still many questions about the case. Books have been written on the subject in the five years since the bombing, positing a number of theories: was Tamerlan an FBI informant? Who was he trying to make contact with in Russia during his 2012 trip? Was he tapped by agents of the FSB? While none of the publications offered definitive proof, these queries still hang in the air.

Unfortunately, I don’t have those answers. I agree that there are a number of strange, unexplainable details about Tamerlan that seem to vanish into the ether. This series isn’t about that. It’s about the concrete facts I’ve been able to gather about individuals who knew Tamerlan, and the possibility that, in lieu of his younger brother, he had other people to conspire with to commit the bombing.

I want to stress I am not accusing anyone of a crime with these posts. I simply want to share my findings and the questions they raise. These are questions that I believe deserve answers, not just for the victims of the Marathon bombing but for all citizens who want to live in a free society, in which justice is administered fairly.

With that in mind, let’s talk about a man who has come to be known by my team as Phone Man. Who is he? Why do we call him Phone Man?

It starts way back in October of 2015, when I found a phone call I couldn’t explain.

The Phantom Phone Call

I can’t quite remember why I decided to look over the cell phone call log on record from the phones of Tamerlan and Dzhokhar that day. I think it was largely in part because the previous autumn, I’d listened to the podcast Serial, and cell phone records played a major role in determining whether murder suspect Adnan Syed could have been at a certain place at a certain time to bury a body. I figured that if cell phone data had been useful in the year 1999, they must be even more so in 2013.

Unfortunately, I also learned cell phone records are both tedious and technically complicated to go through. Everything comprises of a long list of numbers, and without context given in the trial transcript by the government’s cell phone expert, Chad Fitzgerald, I felt hopeless at determining what it all meant.

So I went line by line, following Fitzgerald’s testimony on March 17, 2015, while looking over the evidence report and exhibits. During testimony, prosecutor Aloke Chakravarty and Agent Fitzgerald had focused on the record of the iPhone 4, newly registered through a T-Mobile prepaid plan under the name “Jahar Tsarni” – the phone the government claimed had been obtained by Dzhokhar to carry out the bombing. There was a small number of calls and texts recorded on its account, and I thought surely I could orient myself by following along with Chakravarty and Fitzgerald.

Except suddenly they were talking about a phone call that placed the “Jahar Tsarni” phone in Cambridge the night of April 18th.

Q. Now, is this a slide of April 18th, 2013, the Thursday after the marathon bombing?

A. It is.

Q. And what does this show?

A. So it’s showing both the 9151 phone, the Jahar phone, utilizing a tower kind of over in this side of the map and a sector pointing to the south at 8:17. And I also depicted the two towers and sectors — or three, actually, that were being utilized by the Tamerlan phone starting at 5:34 and ending at 7:30 p.m. So there’s this tower and then two sectors pointing in that direction. And I also put where — I kept on the map 410 Norfolk Street.

Q. And so this shows that 9151 phone number subscribed to Jahar Tsarni, the phone that was activated on the Sunday before the marathon bombing, that was back in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on Thursday at about 8:17 p.m.?

A. I can’t say it was back in. It started being used on the 18th again in the Cambridge area.

Q. And you hadn’t seen any activity prior to that — on that phone before — after April 15th?

A. Right. So the slides I spoke to earlier showing that phone activity, that was it on the 15th, and then it doesn’t get used again until the 18th. (37-38)

Strangely, I realized that Chakravarty and Fitzgerald never covered what number that 8:17 p.m. call connected to. I looked at the corresponding call log and realized it wasn’t a spam text, as previously explained by Fitzgerald, but an actual call to a Boston area phone number, 617-893-1954, for 88 seconds. As Fitzgerald stated, it was the first activity on the phone since the date and time of the bombing on the 15th.

MIT police officer Sean Collier, I remembered, was killed at 10:24 p.m. on the 18th, putting this call approximately two hours beforehand.

So why was it being calmly brushed aside?

I wondered: who could Dzhokhar be calling two hours before Sean Collier was murdered? And why would the government, so eager to tie him to Collier’s death, ignore it like it never happened?

So, I did what any amateur sleuth would do. I googled the number.

I found, of all things, a real estate listing. I wish I’d saved the screenshot, but at the time I couldn’t tell if it was anything significant, so I didn’t think of it. However, I remember the listing was an apartment in Cambridge, MA. The phone number belonged to the real estate agent, Viskhan Vakhabov.

I said, “That sounds Chechen.”

There is not a substantial Chechen community in Boston, so the coincidence struck me. It seemed unlikely that this man had acquired the phone number after the bombing. So I googled his name, too.

I found a news article about Dzhokhar’s trial, dated several months earlier, when it was still ongoing. Mouth agape, I read that Viskhan Vakhabov was a friend of Tamerlan’s, and he was supposed to be a defense witness months earlier. Except he didn’t show.

I remembered from being at the trial myself that the defense had difficulty locating a number of witnesses they had wanted to call, and had to settle for a paralegal sitting on the witness stand and reading from FBI documents about them. It had been confusing to sit there and listen to it. The names of the people were lost from my memory, as it had been difficult to tell them apart without being able to see them. It was also difficult to understand what was so important that the defense insisted the jury hear about them one way or another. (Because of this, I suspect, the effect was likely lost on the jury, too.)

Evidently, Vakhabov was one of these vanished witnesses.

Why didn’t he show up? I wondered. And why, if he was Tamerlan’s friend, was he being called from the “Jahar Tsarni” phone two hours before Officer Collier was murdered?

I will note that I’m not the only one who noticed the anomaly of Vakhabov. Other researchers have had questions about him, including Jill Vaglica of the website WhoWhatWhy and Amy Knight in her 2017 book Orders to Kill: the Putin Regime and Political Murder. To my knowledge, all of us found our information independently. Additionally, my premise is slightly different – I’m looking for accomplices to Tamerlan in lieu of Dzhokhar, not in addition to him. I believe this is an important difference in interpreting the data I’m about to present. And why is that, you ask?

A Bomb is Not a Pot Roast

To properly understand where I’m going with this, we must dive into more cell phone records. I brought up this data and the report made by FBI analyst Chad Fitzgerald in my previous post about the “Jahar Tsarni” phone. Unfortunately, they don’t get sexier or easier to understand from here. You’ll have to bear with me as I explain what I’ve been able to glean from them. Before we do that, however, I need to give some contextual information to explain why I became so interested in an errant phone call.

The first, obviously, is the timing of the call to Vakhabov. While the prosecution was vehement in their “lone wolf” narrative about Dzhokhar and Tamerlan, my study of Collier’s murder had a bunch of discrepancies. The only eyewitness claiming to see Dzhokhar mischaracterized him physically, including by saying he wore a knit cap that was never produced at trial, and neglecting to describe him with facial hair. At first I thought (and even wrote) that the witness, Nate Harman, may have seen Tamerlan instead – but this still doesn’t explain the knit cap. Nor does it explain the forensic evidence of two mismatched golf gloves, discovered in the abandoned Honda Civic with Collier’s blood on them, that were never attributed to Dzhokhar, Tamerlan or Collier. With the surveillance footage showing only two figures and no other details, it’s impossible to say which two figures they were.

And now, with a phone call to Vakhabov before the murder, that throws everything into question. I realized the prosecutors’ need to deny the possibility of outside accomplices: because then the evidence of a second person besides Tamerlan, no matter how vague, always had to be Dzhokhar. But with this phone call, I understood it’s possible Dzhokhar was never at Collier’s murder scene at all.

Second, something occurred to me randomly months after I first found the phantom phone call. I was walking, as I often did back then, near the Marathon finish line, returning from lunch. I was already troubled by the idea of outside involvement with Officer Collier’s murder. At this point, I had recently been sifting through the plethora of evidence recovered at the scene of the Watertown shootout, squinting at evidence photos of the scattered remnants of the escape attempt. As I neared the facade of the Boston Public Library, a thought struck me out of nowhere:

There were three bombs.

In total, there were three pressure cooker bombs in three backpacks. While two went off at the Marathon on April 15, 2013, the third was found partially detonated in Watertown after the shootout. I didn’t know it at the time, but later review of Tamerlan’s purchase receipts showed that this third pressure cooker was one of the ones he bought in Saugus on January 31, 2013, and one of the backpacks he bought at the Watertown Target on April 14th, the day before the bombing.

The possibility rattled me, and was the first inkling I had that maybe the attack the world witnessed wasn’t the one that was planned. Three pressure cooker bombs. Three backpacks.

Did that mean there were supposed to be three bombers?

When I talked to my dad about it shortly thereafter, he agreed the idea had merit. “A bomb isn’t exactly a pot roast,” he quipped. “You don’t make one and put it in the fridge for later.”

He had a point. Making and storing explosives is dangerous business. Why go through the trouble of building an extra and buying a backpack to mobilize it, if you weren’t planning to use it?

At first, I wondered: who could have been the third bomber?

Then, over time, as I learned more about Dzhokhar’s movements beforehand, and how it looked like he was never a conspirator, I wondered: who could have been the second and third bombers? There were pipe bombs made as well, also found on Laurel Street in Watertown after the shootout. All this suggested a larger operation than just two brothers with backpacks. Could there be one, two, or more people out there who devised the attack with Tamerlan and then, for whatever reason, got cold feet? Did Tamerlan decide to push on alone, and knew he could force or dupe Dzhokhar, home from college for the long Patriot’s Day weekend, into getting rid of one more bomb?

I remembered the phone call to Vakhabov on the night of April 18th on the “Jahar Tsarni” phone. I had long been suspecting that although the call was placed on that phone, maybe it wasn’t Dzhokhar who made it. And suddenly I was interested in knowing who else Tamerlan was talking to before the attacks themselves.

There’s just one problem. That information isn’t available on the court record.

The Cell Phone Evidence

And here we are, back at the trial’s cell phone evidence. The only exhibit submitted on the record was the report prepared by Agent Chad Fitzgerald, the same agent who blithely skipped over explaining the April 18th call to Viskhan Vakhabov on the “Jahar Tsarni” phone. Once I realized who this call had gone to, I wondered why it was ignored like it never happened, especially since it came approximately two hours before Collier’s murder. That doesn’t seem like a good time to be calling your brother’s friend to shoot the breeze – especially when the only other activity on the phone was on the day of the attacks. I even wondered, since Dzhokhar didn’t use the “Jahar Tsarni” phone again for days while he was back at UMass Dartmouth, whether the phone was even in his possession anymore.

Because of this erasure of the call to Vakhabov, I felt skeptical about Fitzgerald. Was he really ignorant of who that call went to? In February of 2016, this skepticism was exacerbated. Fitzgerald showed up again, testifying in court in another case I was following: Adnan Syed, of Serial fame. To my surprise, at Syed’s post-conviction relief hearing, the prosecutors called Chad Fitzgerald as their cell phone expert. And, as it was reported, Fitzgerald did not perform very well. He clung to the prosecutor’s assertions even when the defense, on cross-examination, exposed them as absurd. He also outright attacked Syed’s defense attorney about a mistaken attempt at “manipulation” in the original cell report. Which, aside from being unprofessional, actually proved the case the defense was trying to make themselves – that the cover page given to Adnan’s trial defense team had been doctored by the prosecution. But perhaps what worried me most was this egregious misstep, which was summarized by a reporter for The Frisky, Amelia McDonell-Parry, present for the hearing:

Brown [Syed’s defense attorney] asked Fitzgerald when he actually received the documents he needed to review — [the original government cell phone expert] Waranowitz’s 1999 testimony, the cell records and the instructions — in order to give his testimony on the witness stand. … Fitzgerald did not receive any of the documents until days if not a full week after [prosecutor] Vignarajah had already written his disclosure about what Fitzgerald would be testifying to. In other words, Fitzgerald’s analysis was determined before he had done any actual analyzing!

Fitzgerald was flustered and said that he and Vignarajah talked on the phone, and that he agreed — based on what Vignarajah told him about the cell phone records — that Waranowitz was correct in his 1999 testimony. So did Fitzgerald at least READ Vignarajah’s disclosure before it was submitted? No, Fitzgerald said, he did not.

This concerned me because it suggested that Fitzgerald might be content to testify to whatever a prosecutor wanted him to, regardless of the accuracy of the evidence. In Adnan Syed’s case, he certainly didn’t convince the judge. In June 2016, Syed’s convictions were overturned. To date, Syed is still incarcerated, awaiting retrial.

Fitzgerald’s performance at this hearing set me on edge. I returned to his testimony at Dzhokhar’s trial with a more critical eye. Could he be lying about what he was reporting, or at the very least, massaging the truth? However, despite the phantom phone call to Vakhabov, I could find no indication Fitzgerald was claiming anything outright false in his testimony. Although he was vague at times about it, the submitted evidence did match what he had to say.

It’s what wasn’t in the cell phone records that stood out.

In the 14-page report from his FBI unit – called CAST – that Fitzgerald provided, are three phone numbers: Tamerlan’s pre-paid T-Mobile account (ending in 4634), Dzhokhar’s older, existing AT&T account linked to an iPhone 5 (ending in 5112), and the new “Jahar Tsarni” pre-paid T-Mobile account linked to an iPhone 4 (ending in 9151). Unfortunately, this report does not include the names of the individuals these numbers and accounts belonged to, nor their full, respective call logs in a clearly labeled manner. It took me a long time, a lot of back and forth, and an entirely different article about the cell phone evidence before I was able to confidently suss out which phones and numbers and accounts belonged to which brother.

Here is what is in the CAST report: in addition to a cover page, it spends two pages showing pictures of what cell towers look like, and two more explaining how to read call detail records for AT&T and T-Mobile accounts (and provides samples from Dzhokhar’s 5112 phone number and Tamerlan’s 4634 phone number respectively, although their names are attached to neither). The remaining pages are haphazardly laid out maps showing the cell tower pings of cherry-picked calls and data server usage from all three phones in the span of days between April 15 and April 18, 2013. None of these are labeled with names, nor given any kind of context for easy reference.

On top of it all, the actual call log for the “Jahar Tsarni” phone (as well as the other two), that showed who was calling or texting who and for how long, are not in this report. As far as I’ve been able to tell, the call log that I reviewed in October of 2015 came from a chalk provided to Fitzgerald by the prosecutors to use while on the stand. It seems, as well, that this chalk as possessed by the prosecutors was given to the defense in incomplete form. During Fitzgerald’s testimony, defense attorney Miriam Conrad actually stopped the questioning to discuss this with Judge O’Toole:

First of all, I think we’ve resolved the chalk, I’ll call it for now, that Mr. Chakravarty was using, had a page that was not in the one that we had been provided in discovery. So he gave me a hard copy of his, and I now have it. But that was the discovery issue. (45)

It’s difficult to know exactly what the copy the defense had looked like, but it is very strange that it would be missing a page. It certainly makes me wonder if it included the “Jahar Tsarni” call log with the obvious call to Viskhan Vakhabov’s number. I have a difficult time imagining what else it could be, especially since the call log is so sparse that the call to Vakhabov stands out prominently and would not be easily missed.

There’s also the fact that the 14-page CAST report does not list the information of who that call reached, and in conferring with the judge, Conrad states:

I do have some issues about Jencks material. I could ask, if the Court would allow me, Agent Fitzgerald, outside the presence of the jury, about Jencks material. We have been provided no reports, no memoranda, no emails, nothing other than this chalk and the summary expert witness disclosure. No worksheets. (45-46)

In other words, the only cell phone evidence the defense had before trial is the 14-page CAST report I have already described, that was missing a page – most likely the call log that included the call to Vakhabov.

In response, prosecutor Chakravarty insisted nothing was missing:

MR. CHAKRAVARTY: I’ve inquired of him, and there’s no Jencks material that the government is aware of. If Ms. Conrad wants to ask Mr. Fitzgerald that question in lieu of asking in front of the jury, then the government has no objection to it. (46)

So that’s what Conrad did. Without the jury present, Conrad asked Fitzgerald the following:

Q: In preparing what the jury has now seen, the multiple-page, I think 14-page document, did you take any notes in preparation of that?

A. No. It’s all just done on the computer utilizing the records and the tower list and the mapping and so forth.

Q. And do you create spreadsheets as you’re doing that?

A. They’re just derivative of the original spreadsheet. So they might be pared down to, like in this case, the April 15th through the 18th, but there’s no — I don’t create an original spreadsheet, no. (46)

As you can see, here Fitzgerald is admitting that there was a much larger record, and that he “pared down” a “derivative” version that went into the report and to the jury. Conrad goes on to ask:

Q. Well, you created documents that were essentially a summary of what you reviewed, the records you reviewed. Is that right?

A. I utilize the records, the original call detail records, and then I can filter it out — or filter it down to the calls I’m interested in versus having the thousands of calls.

Q. I see. All right. And did you write any reports or memoranda regarding what you found?

A. No. I mean, I’ve emailed back and forth like the drafts and stuff like that for peer review or to the prosecutors.

Q. So when you say “drafts,” drafts for what?

A. The presentation. (47)

Again, Fitzgerald is stating that he did all this paring down for one purpose: for the prosecution team, and the 14-page CAST report is the only cell phone evidence that the prosecutors wanted. Conrad continues:

Q. How many drafts did you prepare?

A. I only sent one draft up to Al. I mean, that’s the draft. I mean, that was the draft, and that draft becomes a final.

Q. And you said there were emails back and forth?

A. Right. To the person who is doing the peer review, asking them to do the peer review, as well as to Al, showing him that the draft was done and to contact me after he reviewed it.

Q. And was there any substance in those emails?

A. No, it was all logistics.

Q. Okay. Thank you. (47-48)

So, as he says, he only sent one draft to “Al” (Aloke Chakravarty) of a “pared down,” “filtered” “derivative” of the much larger cell phone record spreadsheet. Recalling Fitzgerald’s practice with the prosecutor in Adnan Syed’s case, it does make me wonder what the “logistics” they discussed might have been, or what else they might have spoken about not in email regarding the crafting of this report. Because if one thing is clear here, it’s that my reaction to the CAST report and the defense’s reaction must have been identical: this is it? Why is so much missing? The kicker is that while I’ve struggled for years to make sense of the records, I didn’t realize that the defense actually had less data to work with than I did. In that respect, no wonder the call to Vakhabov went unchecked.

Of course, the trial is long over by now, and through the unsealing of documents from the court docket, I have some more data regarding the cell phone evidence that wasn’t in Fitzgerald’s CAST report. I was hoping, maybe, with more complete records, I could glean a little more about what was going on, especially when it came to Tamerlan’s phone.

Unfortunately, that is difficult. Especially when I realized the records from Tamerlan’s phone start the afternoon of April 15, 2013.

This is, in fact, the phone call from the “Jahar Tsarni” phone just before the first blast on Boylston Street. There is nothing at all before that.

Which in and of itself is weird, especially considering this was a conspiracy case. I always wondered, wouldn’t the prosecution want to have the call logs from before the attacks, you know, to line up with all those times Dzhokhar and Tamerlan were allegedly getting together to build explosives? In fact, there is none of that. In the process, because we’re supposed to be focusing on Dzhokhar, Tamerlan’s pre-bombing movements are erased.

I’ve twisted my brain every which way for years to try to find a plausible explanation for this. While it could be that the FBI simply weren’t looking at the calls and texts of a terrorism suspect before the attack was committed, that seemed laughable on its face.

It also defied the description Fitzgerald gave about the investigation himself. On the stand, while under direct examination by prosecutor Chakravarty, Fitzgerald laid out how the CAST unit did their analysis:

Q. And were you involved with a portion of the investigation back in April of 2013?

A. I was. I came here fairly quickly.

Q. Okay. And was the CAST team deployed to Boston to assist in the investigation?

A. Yes. There were several members here — both assigned members and people that we have in training, both came here. I’m not sure — when I was here I think we had somewhere in the neighborhood of five to six people on CAST, and then we got relieved with another wave of people after about a week or so.

Q. And particularly with regard to what your analysis was for presentation to the jury, is that a small subset of all of the analysis that was done over the last two years?

A. Absolutely. I mean, this is pared down to keep it — try to keep it somewhat simple. (10)

It definitely doesn’t seem to be that the CAST team didn’t investigate Tamerlan’s calls before the afternoon of April 15, 2013. Apparently, “somewhat simple” equates to stripping the record of as much of Tamerlan’s call log as they could. This makes Fitzgerald’s skipping of the April 18th Vakhabov call even more sinister – did he understand what the call meant, but didn’t explain because then the story would no longer be “simple”?

Things get weirder. In looking through the CAST report, I found the previously mentioned pages near the beginning, which are seemingly included to explain what all the parts of a call log mean to a reader. Although one of these pages is labeled “Explanation of T-Mobile Call Detail Records,” the short list used Tamerlan’s phone as its sample log. The eight calls listed were all made on April 10, 2013. As far as I can tell, this was used as a random sampling by Fitzgerald, and was not meant to be presented as “real” evidence.

I squinted at the numbers in this random sampling, and my mouth dropped open.

Viskhan Vakhabov’s number, 617-893-1954, showed up three times. Once as a voice call, and twice as texts.

Tamerlan was talking to Vakhabov, on his own cell phone, five days before the bombing.

Which might not be weird on its own, except that he was also called two hours before the murder of Officer Collier and the prosecution didn’t seem to want to talk about it. And there’s more.

On the court record, in an interview with the FBI, Vakhabov had denied speaking to Tamerlan since at least a month before the bombing.

Pants on Fire

At this point, I wanted to know everything on the court record about Vakhabov. The evidence was piling up, and his absence from the trial started looking stranger and stranger. First, I went back to the FBI 302 read by the defense’s paralegal, Sonya Petri, on April 28, 2015.

If you aren’t familiar with an FBI 302, it is a memo written up by investigating agents after interviewing witnesses and persons of interest. As a rule, the FBI do not record their interviews. This practice has garnered criticism over the years because we can never be sure how well an agent’s summary reflects the reality of a situation. Additionally, these 302s read by Ms. Petri during the penalty phase were also partially redacted. These were done by the defense because they contained information that the government objected to.

Regardless, this FBI 302 is the closest thing we have to knowing what Viskhan Vakhabov told investigators. The reading of it was conducted by Miriam Conrad, and starts as follows:

Q. And who was interviewed — what interview is reflected in this?

A. The interview of Viskhan Vakhabov.

Q. And when did that occur?

A. April 20, 2013.

Q. Where?

A. In Allston, Massachusetts.

Q. And who conducted that interview?

A. Jeffrey F. Hunter.

Q. And where did the interview specifically take place?

A. At Vakhabov’s residence. (145)

Most of the account is general biographical information about Vakhabov and how he came to know the Tsarnaev family. He was born in Chechnya but because of the devastation of the Second Chechen War, his family immigrated to Chelsea, MA through a United Nations program. His parents and Dzhokhar and Tamerlan’s parents knew each other through the immigrant community. Vakhabov would hang out with Tamerlan, and “They would smoke, drink and go to clubs. Tamerlan Tsarnaev introduced Vakhabov to some of his ‘weed’ smoking friends in Cambridge”(147). Vakhabov has a younger brother named Israpil, who attended UMass Dartmouth with Dzhokhar. However, about two years prior, Vakhabov stated he noticed a change in Tamerlan’s behavior:

Tamerlan Tsarnaev told Vakhabov that a true Muslim would not go out and smoke and chill out. Tamerlan Tsarnaev told him that just because you say you are a Muslim, it does not mean that you really are.

He knew about Tamerlan’s trip to Dagestan, but did not know the purpose of the trip, although he did admit that “Tamerlan Tsarnaev telephonically contacted Vakhabov one time from Dagestan”(148). However, according to Vakhabov, after Tamerlan returned in July 2012:

He has spoken with Tamerlan Tsarnaev approximately four to seven times since Tamerlan Tsarnaev has returned to the United States. Tamerlan Tsarnaev would tell him that extremist violent jihad was the proper path. …

Approximately four weeks ago, Vakhabov provided a ride home from UMass Dartmouth for his brother, Israpil Vakhabov, and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. Upon arriving at Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s home, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev invited Vakhabov inside. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev told Vakhabov that Tamerlan Tsarnaev was inside and wanted to speak with him. Vakhabov did not want to go inside because he felt Tamerlan Tsarnaev was likely to try to teach him about religion or to criticize his religious practices. Vakhabov attempted to telephonically contact Tamerlan Tsarnaev from his vehicle outside the residence. However, Tamerlan Tsarnaev’s number was disconnected, and Vakhabov deleted the number from his cellular telephone. (148)

I read this over and over, scarcely able to believe what I was seeing. Apparently, Vakhabov told the FBI he had barely spoken to Tamerlan in nine months, and had effectively cut ties with Tamerlan a month earlier, and didn’t even have his current phone number.

But I had evidence of phone correspondence between them just days earlier.

When I first heard this information in the courtroom, I wasn’t sure what it meant, other than an obvious theme that had run through everything at trial – Tamerlan was so aggressive in his extreme beliefs that he had pushed friends away; Dzhokhar, a family member, hadn’t been able to escape his orbit.

But no one ever brought up the phone calls and texts to Vakhabov. It seems now that the defense had missed them, perhaps because of deliberate deception. Regardless of why, this is completely different from mitigating evidence that Tamerlan was so vile he had infected Dzhokhar. This is evidence of Tamerlan’s friend lying to the FBI about being in contact with him – at least once days before the bombing, and probably again, just two hours before Sean Collier was murdered.

I had to ask: what did Vakhabov have to hide? And why was everyone in the government so okay with it? As recent headlines have proven, lying to federal investigators is a very serious offense. And Robel Phillipos, Dzhokhar’s friend, just spent three and a half years in federal prison for lying to the FBI about when he’d last seen Dzhokhar.

What’s so special about Viskhan Vakhabov?

I don’t know, honestly. Even after three years, I still don’t know.

But I do know that at trial, the prosecutors knew about him.

Matters of Great Import

After this discovery, I scoured the rest of my archived court record for mentions of Vakhabov, to see if I could find any indication of why he was not available to testify like the defense had wanted.

I quickly discovered a lobby discussion, out of earshot of the jury, between prosecution, defense, and Judge O’Toole regarding Vakhabov’s refusal to testify on April 27, 2015. In lieu of that, the defense wanted to present the FBI 302 that I have already quoted. However, the government objected. In that conversation, prosecutor Bill Weinreb provided a number of interesting details about what happened to Vakhabov. In particular, the government had an objection to the admission of the 302 because, in their words, he was an “unreliable witness.” Why, exactly? Well, according to Weinreb:

He gave several statements to the FBI over time before he was called to the grand jury, in which he gave inconsistent statements and statements about matters of great import. I think it’s undisputed that Tamerlan Tsarnaev contacted him on April 18th, I believe, between the time that Officer Collier was murdered and the time that Dun Meng was carjacked. And he has given quite inconsistent statements about what that conversation was about and about what Tamerlan Tsarnaev may have asked him or said to him. (13-14).

This quote knocked me flat.

First, it confirmed what I had been long suspecting: that Tamerlan had placed the call to Vakhabov from the “Jahar Tsarni” phone. In fact, this raises a lot of questions about that phone. In a previous post, I hypothesized that perhaps Tamerlan provided the new iPhone 4 for Dzhokhar, and that might account for why the last name on the phone account is “Tsarni” – the original Chechen form for the surname Tsarnaev. Tamerlan considered adopting this form of the name, but no evidence exists that Dzhokhar ever did.

Also, I noticed that after April 14th and April 15th, all activity on the “Jahar Tsarni” phone halts until that call to Vakhabov on April 18th. I always had a difficult time believing that a nineteen-year-old would get a brand new smartphone to replace one whose service had been shut off, only to stop using it – unless he had a really good reason. I have wondered if perhaps after being forced or manipulated by Tamerlan into participating in the bombing, Dzhokhar didn’t want him to have any more favors to hold over his head. Therefore, he didn’t take the “Jahar Tsarni” phone back to UMass Dartmouth. Whether this is a plausible explanation or not, the cell phone evidence does back this up – there is no data placing the “Jahar Tsarni” phone at UMass Dartmouth. The 8:17 p.m. call to Vakhabov is placed from near Tamerlan’s residence in Cambridge, MA.

Addtionally, not only do the prosecutors state that it’s “undisputed” that Tamerlan called Vakhabov that night, but that Vakhabov lied about it, and that Tamerlan may have “asked” him something. What on earth could he be asking for, two hours before committing a murder?

It is important to note, Weinreb gives one inaccurate detail – he states the call happened after Collier’s murder. However, by the prosecution’s own timeline, Sean Collier was shot at 10:24 p.m. on April 18th. With the Vakhabov call coming at 8:17 p.m., I must stress that this is very much before Collier’s murder – two hours and seven minutes before, in fact. Definitely long enough to call your friend in Allston and ask him to come over to Cambridge to help you with something, for instance. I don’t know whether Weinreb was misspeaking, genuinely mistaken about the time, or being misleading in his statement, but the fact remains: there is no way this call to Vakhabov came after Collier was already dead.

Understanding that the government knew this information about Vakhabov and his story that doesn’t match the evidence, one must wonder: why wasn’t he forced to testify?

At the time, in fact, a reason was given. But it didn’t make any sense.

The Fifth Amendment

At that same lobby conference on the 27th, Weinreb states, “Up until Saturday [the 25th] at 8:30, we have been under the understanding that Mr. Vakhabov was going to take the stand and testify.” However, in light of his refusal to show up, Weinreb said the government didn’t want anything from his FBI interview to go to the jury. Why?

Mr. Vakhabov, we object in particular — in addition to our general objection, we object in particular to any 302 of Mr. Vakhabov coming in because he is an unreliable witness. He is someone who refused to testify in the grand jury on the grounds that his testimony might incriminate him. My understanding is he’s informed the defense — or his lawyer has informed the defense that he would do the same if called at this trial. (13)

This is, in fact, the information that made it to the press during the trial, and was reflected in the article I found way back in October 2015 when I first googled Vakhabov’s name, that “Judge George O’Toole told jurors Vakhabov would plead the Fifth if called to testify.” It seemed strange to me from the get-go, because, despite not knowing much about the Fifth Amendment, I knew one thing: it was the right against self-incrimination. As in, you yourself can’t invoke it unless you could be implicated in a crime with your answers. Prosecutor Weinreb seemed concerned about the same thing:

He’s not a disinterested third party in this case. On that ground, we believe that this is just putting information before the jury that is much more prejudicial than probative. It creates too much of a chance that they will be misled, confused, and so on. (14)

“Misled” into what? I wondered. Into thinking maybe there’s someone else who could have committed the crime besides Dzhokhar? That didn’t seem prejudicial to me – it seemed potentially factual.

Additionally, no one at trial or in the media ever commented on Vakhabov’s intention to plead the Fifth the way my father did. When I told him about it, he said, “You can’t just claim to take the Fifth and get out of testifying.”

“Why not?” I asked, surprised.

“The Fifth Amendment is the right against self-incrimination, so you cannot be forced to testify against yourself,” Dad said. “But he’s a witness, not the defendant. Only the defendant has an automatic blanket right not to testify. As a witness, you cannot tell the judge, ‘I’m gonna take the Fifth’ and everyone says, ‘Okay, don’t show up.’ What? Was there a subpoena?”

“I don’t know,” I said, more confused than ever.

“His lawyer may have said they intended to quash the subpoena. That might be what they’re referring to on the record.”

I haven’t found specific evidence in the record that Vakhabov was issued a subpoena, although other witnesses who testified for the defense in the penalty phase were. But I did find the transcript of Judge O’Toole’s instructions to the jury about Viskhan Vakhabov before Sonya Petri read the 302 about him on April 28, 2015. Here is what he said:

Mr. Vakhabov indicated that if he were brought here, he would invoke his Fifth Amendment privilege not to testify as to matters that might incriminate him. And that made him unavailable for testimony here because that invocation would be respected. (150-151)

To try to understand this, I turned to the law – namely, a book at my university’s law library. In The Privilege of Silence: Fifth Amendment Protections Against Self-Incrimination, authors Steven M. Salky and Paul B. Hynes, Jr. lay out all the case law for the right to invoke the Fifth Amendment. They state that that only forced testimony of self-incriminating information is protected by the Fifth Amendment and that “Information is self-incriminating if it may subject the speaker, or lead to other information that may subject the speaker, to the possibility of criminal prosecution or penalties”(11). They also note that the Supreme Court has set the bar for invoking the Fifth rather high, when “the claimant is confronted by substantial and real, and not merely trifling or imaginary hazards of incrimination”(11-12).

In other words, in order to take the Fifth, you can’t just be a paranoiac – there has to be a tangible cause to invoke it that is known to the government. Fear of unjust treatment or a general disdain for showing up to court wouldn’t cut it.

Here is what Salky and Hynes have to say about the Fifth Amendment in the case of a trial witness, like Vakhabov was intended to be:

A witness’s Fifth Amendment right not to testify generally trumps a defendant’s Sixth Amendment rights to compulsory process and to present a defense. Thus, most courts have denied attempts by the defendant to call a witness to the stand who intends to assert the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination. (103)

So in this case, Vakhabov’s right not to incriminate himself on the stand overrode Dzhokhar’s right to due process. This sounded a little strange to me, until I started reading the case law involved. For example, the most recent ruling comes from United States v. Santiago, 556 F.3d 65, 70 (1st Cir. 2009): “Defendant has no right to compel a witness who will legitimately assert the Fifth Amendment to all questions to take the witness stand”(103).

This is when I started to understand: to all questions. As in, there is absolutely nothing to be asked of the witness that he could answer. This means that it’s unlikely any relevant questions posed to the witness would involve crimes other than the one for which the defendant is being tried. As Salky and Hynes write:

Numerous courts have prevented the government from calling an alleged participant in the crime as a witness, knowing or suspecting that the witness will assert his Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination, either as a violation of the defendant’s Sixth Amendment right to confront his accusers or as evidentiary violation. (104, emphasis mine)

So the only way Judge O’Toole was able to recognize and honor Vakhabov’s refusal to appear due to the Fifth Amendment is because the government had good reason to believe Vakhabov was a part of the crime Dzhokhar was on trial for.

One must ask: which part? Terrorism? The murder of a police officer? Carjacking? How come, if their suspicion about Vakhabov was so good that he didn’t have to testify at Dzhokhar’s trial, was he not under indictment himself? Just how much did the government know about Viskhan Vakhabov that they let slide?

The bottom line is, if Judge O’Toole signed off on this, and he would have had to, there should be some mention of it on the official court record. I haven’t found any, which means either it is still under seal, or it was not done on the record, which is reversible error and grounds for appeal. Still, that doesn’t answer the remaining question: what exactly would Vakhabov have incriminated himself about if he’d testified?

Vakhabov and Tamerlan’s Past

In trying to answer this, I knew I just had to keep looking. Vakhabov – by now often referred to by us as “Phone Man” – resurfaced time and again, as I went about other research. When I first found Tamerlan’s call to Vakhabov, there was so much about Dzhokhar I didn’t know. But as I focused on Dzhokhar, I was able to systematically eliminate him from allegation after allegation. As the months and then years passed, he began to look more and more innocent. And yet, every time I came back around to Vakhabov, all the questions not only remained, they compounded.

About a year and a half ago, I began to compile my list of Unusual Suspects, and Vakhabov was at the top of it. Still, I didn’t want to write about him yet. I know there are some very serious implications here, and I didn’t want to be wrong. I didn’t want there to be some easy explanation I could find after smearing an innocent bystander. But to date, I haven’t been able to explain any of this information, and the the more I learned, the thicker the plot became.

After discovering Vakhabov’s mysterious vanishing act from trial, I wanted to know what else I could find out about him, especially in regard to his relationship with Tamerlan. Other than the questionable content of his FBI interview, the most interesting piece of information about Vakhabov in the court record doesn’t come from conversations or 302s about him. It comes from a defense witness in the penalty phase – and indirectly, at that. On April 28, 2015, the defense called a man named Rogerio Franca to the stand. He is a Brazilian immigrant who knew Tamerlan through friends. He even lived close by in Cambridge, rooming with one of them from the years 2008 to 2011. During this time, he hung out with a close knit group – his roommate, Abubakr Turshaev, Tamerlan Tsarnaev, and Viskhan Vakhabov. There were even pictures.

Interestingly, I almost missed these details in the transcripts because of a clerical error – Franca never named Vakhabov by his last name, and in this section of the transcripts, under direction examination by defense attorney Tim Watkins, his name was either mispronounced or misspelled, showing up as Vishkan, not Viskhan:

Q. Could you go through that again and identify each of those people in the picture?

A. This one is Tamerlan, this one is Vishkan and this one is Abubakr Turshaev.

Q. And Abubakr Turshaev, he was your roommate?

A. Yes.

Q. Vishkan Vakhabov, did he actually live at Harding Street at that point?

A. Who? Sorry.

Q. Vishkan Vakhabov.

MR. WEINREB: Objection, your Honor. No last name was ever given for that individual. (13)

Despite not knowing Vakhabov’s last name, Franca had specific recollections of Vakhabov and Tamerlan coming to his apartment.

Q. What kinds of things would Tamerlan Tsarnaev do when he came over to your home that you saw?

A. He used to come a lot to my home. He used to smoke weed in my basement. He used to come home to this — Abubakr, Vishkan, he used, you know, to call them to go outside to party in Boston sometimes.

Q. The three of them, would they go clubbing —

A. Most of the time, yes.

Q. — in Allston?

Now, is that something that you liked to do?

A. I don’t like to go outside that much like they like it.

Q. Do you smoke marijuana yourself?

A. No.

Q. And do you enjoy alcohol? Do you drink?

A. No. (14-15)

Aside from some lifestyle differences, at times, Franca did not have flattering things to say about Tamerlan and his friends. Tamerlan was at the apartment around noon until late at night, on weekdays and weekends. Franca did not know Tamerlan to have a job besides occasionally helping his father, a car mechanic. Often he came home from work to find Tamerlan smoking marijuana in his basement, despite Franca’s direct requests not to. Another time, this happened:

Q. Was there a time when you came home and Tamerlan was doing more than just smoking marijuana?

A. Yeah, one day I came from my job, and I met him inside my room, him and the other ones inside my room.

Q. Let me stop you there. Inside your bedroom?

A. Yes, inside my bedroom.

Q. And he and the other ones, what do you mean by that?

A. I guess they was dividing some drugs inside the room

there, on a table inside my room.

Q. And what makes you say that they were buying drugs?

A. Excuse me?

Q. Why do you say that they were buying drugs?

A. They was not — I don’t know if he was buying or they were dividing drugs right there.

Q. Oh, dividing drugs?

A. Yeah. Like weighing the drugs inside.

Q. And you could see that they were dividing drugs?

A. Yup, inside the little bags.

Q. And what did you do?

A. I just told everybody get out of my room. That is no place for them to do that.

Q. And did they leave at that point?

A. Yeah, after a few minutes they did. (18-19)

This section is a little difficult to parse, mostly because of Franca’s limited English. However, given the context, he seems to be saying that Tamerlan, Vakhabov, and Turshaev were sitting in Franca’s bedroom, dividing up drugs – probably to sell. He does not specify what kind of drugs, and I wish we knew more information. However, earlier in his testimony Franca seemed to make a clear distinction about marijuana – he calls it “weed.” Because he does not specify the drugs he saw Tamerlan and the others divvying up, it’s possible they were a separate substance from marijuana. Regardless of the product, this seems to put Tamerlan and Vakhabov in some sort of illicit trade together.

While Tamerlan’s ties to the drug trade have been largely overlooked, I have raised questions about them in the past. In particular, in regard to the chain of custody of the Ruger P95, used to kill Sean Collier, I discussed the possibility that Tamerlan had ties to a drug gang operating out of Portland, Maine, that saw the flow of crack cocaine into Boston. I won’t rehash the finer points of that article here, but this seems to be another glimpse into the life Tamerlan was leading in the years before the Marathon bombing. Additionally, this eyewitness account implies Vakhabov may have been in the same sort of business. This makes the phone call to Vakhabov on April 18th at 8:17 p.m. more interesting, as Collier was murdered by the Ruger two hours later. The prosecutors were adamant that Dzhokhar provided Tamerlan with the murder weapon, but the only person to testify to it was an incentivized witness bearing inconsistent testimony and the likelihood of perjury. A separate law enforcement investigation only wanted to know how the Ruger got from the Portland gang to Tamerlan without Dzhokhar as a middle man.

One must wonder what exactly Tamerlan asked Vakhabov for when he called that night.

Chasing Tamerlan

As I started to compile the persons of interest in this case, it struck me as never before how difficult the current court record makes it to track Tamerlan’s movements. His phone records start the afternoon of April 15th; we don’t have access to any financial information like bank statements; there’s no access to emails or texts to anyone who isn’t Dzhokhar. There is, in fact, very little we know about Tamerlan through the court record that doesn’t involve his religious fervor. Over time, I have become increasingly been frustrated by this, especially as someone now studying the phenomenon of Islamophobia in my graduate work. The West, and America in particular, has a long, colorful history of vilifying Muslims, boiling them down to nothing more than vessels of divinely-inspired rage. This was easy to observe in the prosecution’s characterization of Dzhokhar, because according to everyone who knew him, he was not radicalized. However, in recent months, I realized Tamerlan was also subjected to this, despite the likelihood that he was.

I have come to suspect that law enforcement and policy-makers alike miss the forest for the trees when they point their fingers at “radical Islam” as a criminal motivation. Yes, multiple people saw a change in Tamerlan as he grew more religious. Yes, he became pushy in his beliefs on Islam, idolized the Islamic-flavored Chechen resistance movements, expressed solidarity with slaughtered innocents in Syria. But in a journal laden with Quran quotes, his last entry was his daughter’s name five times. He sold drugs, and possibly harder drugs, a risky business. Did no one in law enforcement wonder if he had any debts? Did anyone check his bank statements? Even ISIS offers soldiers a salary. And did no one ask, with three pressure cookers and three backpacks and a multitude of gunpowder appearing out of nowhere, what his social network looked like beyond the kid brother who was away at college?

Allah alone is usually not a sufficient criminal motivator. Many people in the West claiming to be experts have tried to argue that it is, but their points of view are laden with white supremacy, remnants of a colonial age we haven’t quite disentangled ourselves from yet. I can’t know for sure what law enforcement didn’t look for because knowing Tamerlan was an angry Muslim was enough, or what the prosecutors may have obfuscated because it would have made Dzhokhar look like a scared kid and not a jihadist monster. However, I found myself not caring about what either Tsarnaev brother believed. I want to know what they did. As I have found, Dzhokhar has done basically nothing. Maybe it was time to offer Tamerlan the same courtesy.

This was difficult, as I said, because there isn’t much useful about Tamerlan available on the court record. On top of gaps in what should be easily available information like phone records, the vast majority of filings by both prosecution and defense regarding Tamerlan have huge swaths of redactions. There seems to be a lot about him the government still doesn’t want the public to know. If, as they have assured us over and over, this was truly a lone wolf attack, what is there left to conceal?

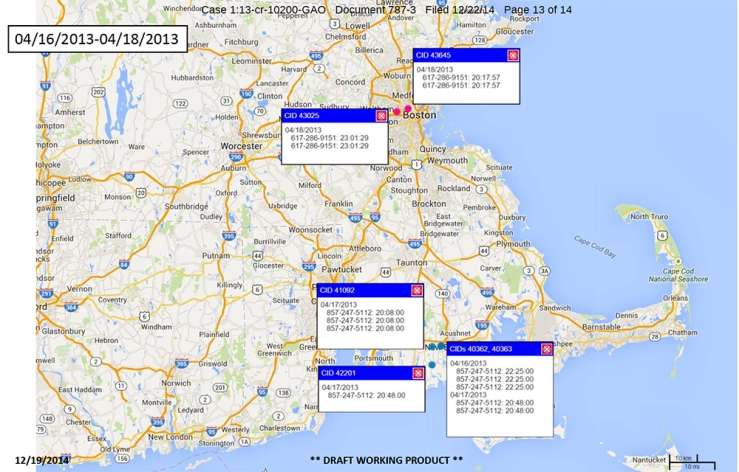

Despite numerous dead ends, there was one thing I realized I could do: use the information that had fallen through the cracks. In studying the CAST report provided by Agent Fitzgerald, I learned that the call log records the GPS location of the cell tower the call pings when it connects. His report includes a map of these cell tower pings, including the same tower on Boylston Street both Tamerlan’s phone and the “Jahar Tsarni” phone pinged shortly before the explosions on April 15th.

If Dzhokhar called Tamerlan from about a block away, it makes sense that both cell phones pinged the same tower. However, I realized there were definitely data points that were not mapped out by Fitzgerald: the “random sample” call log from Tamerlan on April 10th. And that call log conveniently provides the latitude and longitude of the cell towers pinged.

I decided to start plugging the cell tower latitude and longitude into a geo-location site I found through Google, and find out where he was when making those calls.

A few notes about cell phone technology before I go any further (and, as a disclaimer, I myself am not a cell phone expert): as a rule of thumb, cell tower pings can’t give you someone’s exact location, but they can give you a ballpark figure. It is not guaranteed to ping the closest tower location, but it should ping somewhere in the immediate vicinity. In an urban center like Boston, with many cell towers to serve a dense population, it will probably give you a closer estimate than somewhere out in the wilderness, where one tower may cover several miles. Additionally, text messages (listed as SMS on the log) use internet data and don’t ping cell towers; only actual phone calls do.

In the interest of full disclosure, I will say I mapped out the cell tower pings from the “random sample” of April 10th calls from Dzhokhar’s AT&T phone as well. They placed him at UMass Dartmouth for all of the calls, which cover the evening of the 10th into the morning of the 11th.

There is one call from Tamerlan late that night, at 12:27 a.m. on the 11th, and they talked for about a minute. But this, along with everything before April 15th, is never mentioned by the prosecutors. And, honestly, there is nothing inherently suspicious about this: they were brothers, and Dzhokhar was home from college in Cambridge by the 12th for the long weekend, and it stands to reason they probably talked about it at some point.

In contrast, in Tamerlan’s April 10th call log, he received four voice calls, and none of them were from Dzhokhar. Actually, all came from the same Boston area number, 857-488-0727, at 12:18 p.m. for 76 seconds, at 12:25 p.m. for 39 seconds, at 4:26 p.m. for 49 seconds, and at 5:40 p.m. for 73 seconds. I have not yet been able to track who this number belonged to.

Then there is one outgoing call to Vakhabov, at 5:28 p.m, in which they talk for 44 seconds. Later that night, Vakhabov texts Tamerlan at 9:38 p.m., which Tamerlan answers at 9:40 p.m. (T-Mobile lists its text times in Pacific time, so I added three hours to get them to Eastern Standard Time, Boston’s time zone.) The final text is from an unknown number which looks foreign, as it has extra numbers than American ones, at 10:51 p.m.

Mindful of the insistent mystery number, I started plugging in GPS coordinates for each call going down the list. Most pinged towers in Cambridge near Tamerlan’s Norfolk Street residence, which was fairly mundane. I started to think maybe this would be another dead end.

Until I got to the third incoming call from the mystery number at 4:26 p.m.

I plugged in the GPS coordinates, and the map I was looking at shot to downtown Boston. Tamerlan had moved in the four hours between calls. I recognized a familiar building, the Boston Public Library on Boylston Street.

Near the Marathon finish line.

I literally leapt out of my chair.

On April 10, 2013, the same day he Googled “Boston Marathon,” Tamerlan Tsarnaev visited the crime scene.

In fact, the GPS coordinates I plugged in matched Chad Fitzgerald’s report that mapped out the cell tower Tamerlan’s phone and the “Jahar Tsarni” phone both pinged directly before the explosions. Additionally, having worked close by, I suspect that set up for the Marathon likely would have started by the 10th. In 2014, for instance, I made a Facebook post about avoiding the area because of heightened security on April 11th, when the race wasn’t until the 21st that year. I could find no indication in news coverage of the 2014 Marathon that they were setting up any earlier than usual, just that police presence was heightened.

While Tamerlan was on Boylston Street near the finish line, likely during the set up for the Marathon, someone called him, and they talked for almost a minute.

And the next person he called, at 5:28 p.m., was Viskhan Vakhabov.

What Does It All Mean?

That’s an excellent question. For three years, I’ve tried to understand it myself. Over time, it hasn’t gotten easier. In fact, the opposite has been true. Because as I have been able to eliminate Dzhokhar as a suspect time and again, my understanding of the case’s narrative has shifted. It wasn’t the brothers Tsarnaev, jihadist partners in crime. It became more complicated than that, and obviously so. Tamerlan didn’t mastermind the plan; he collaborated with someone or someones who were not Dzhokhar. A bomb is not a pot roast – you don’t build one and buy a backpack for it the day before unless you plan to use it. Whoever the other accomplices were, and why they were not available to set the plan in action, I don’t know. But Dzhokhar was never intended to be one of the bombers.

If that’s obvious to me, a layperson pouring over scraps, I must ask: why was this ignored by the government? Why was the call to Vakhabov on the “Jahar Tsarni” phone brushed off during testimony? Why was it known to the prosecutors that Vakhabov lied to the FBI about “matters of great import” the night Sean Collier was murdered? Why did the government honor his Fifth Amendment right not to incriminate himself in the crime Dzhokhar stood trial for, then let him off the hook while Dzhokhar faced the death penalty? Why does Tamerlan’s call log on the court record start on April 15th, right at the time of the attack? Why does Dzhokhar have to keep paying, and paying, and paying, when at the end of all this he looks like the most innocent one here?

I don’t have those answers. I’m hoping maybe you can tell me. Because I have wracked my brain for three years and I still can’t be sure.

I welcome input. I would love to hear from Viskhan Vakhabov. I’m not accusing him of anything. I just want answers. Why didn’t you testify before the Grand Jury or at Dzhokhar’s trial? What did Tamerlan ask you the night of April 18, 2013? What did he tell you on April 10th after he visited the place where he would detonate a bomb five days later?

I think the public deserves to know all this, and more. At the very least, I can offer what no one offered to Dzhokhar: I’m willing to listen.

One Last Thing

I have played the actions of the Boston Marathon bombing in my head hundreds, if not thousands of times over the last five years. My understanding of it has changed fundamentally since then, from the sterilized, government-approved version, to the chaotic mess that it undoubtedly was. I know I offer more questions than answers. I know that this blog has been better at disproving Dzhokhar’s involvement with the crimes than it has been at explaining anything else. I know I don’t have a smoking gun I can place in Vakhabov’s hands – or anyone else’s. I’ve learned we probably will never have smoking guns in most cases like this, just little details that start to add up. I’m sorry this labor of three years is barely more than bread crumbs.

I confess this is the scariest aspect of my work on this case. When I started, I thought all I would have to do was determine the level of Dzhokhar’s culpability, and debate, perhaps, what punishment he deserved as a result. I never thought I would learn the case was still unsolved, and have to solve it myself.

The worst part of this is the seemingly endless possibilities. As stated earlier, confining all the actions to two perpetrators forces a simpler version of events: it either had to be one brother, or the other. But eliminate Dzhokhar and the scenarios multiply. You can never trust any assumption anyone in the case has ever made. For example, who says Dzhokhar and Tamerlan were at the Marathon alone? What if Tamerlan had said he wanted to meet someone, had to give him something, and if Dzhokhar could just carry this backpack they would meet up and exchange? What if Tamerlan stepped away from Dzhokhar, saying he had this person to meet, and he’d be back? So Dzhokhar put the heavy backpack down by a tree, and watched the Marathon, like thousands of other spectators, until he began to wonder where his brother went. So he picked up his new phone and called his brother to ask, “Where are you?”

At this point, that’s just as possible as anything else. There’s so much we don’t know. And the ability to narrow it down has been taken from us, because the trial laser-focused on Dzhokhar so that we wouldn’t ask questions about Tamerlan.

It may be impossible to sort out the timeline of an attack that involved several thousands of people, but there’s a different series of events that went virtually unexplored at trial that might be easier to suss out. While I’ve researched and written a great deal about the murder of Officer Collier on the night of April 18th, I’ve barely touched what happened afterward. I’ve been interested in the carjacking of Dun Meng, which led to the shootout in Watertown, since – well, since the morning I woke up and was told I should stay inside my home because a nineteen-year-old terrorist from Cambridge was on the loose.

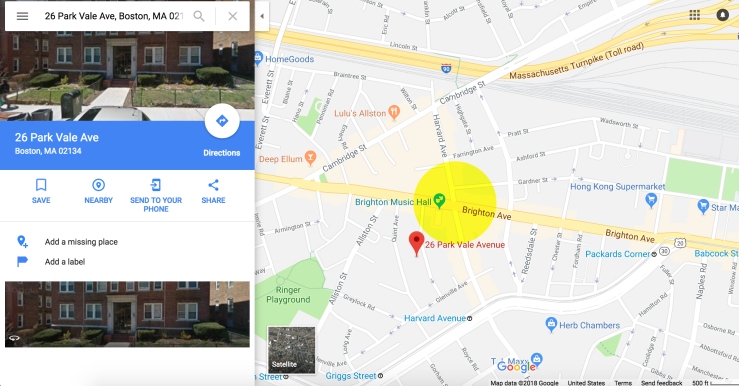

I must save an actual analysis of the carjacking for next time, because in the light of recently discovered information, more investigation is needed. However, back in February of 2017, when we weren’t sure what we were looking for, I took a car trip with friend and field investigator Eric Bowsfield. Our goal was to recreate the carjacking route from Dun Meng’s testimony. We tried to link it up with the facts of Sean Collier’s murder. He was killed at 10:24 p.m. on MIT’s campus in Cambridge, and at approximately 10:45 p.m., Dun Meng was approached by Tamerlan with a gun in Allston. He testified he was on Brighton Ave, near the cross-street Harvard Ave, which would put him right near a place known as Packard’s Corner.

As Boston resident, this fact always bothered me. Allston is in no way a straight shot from Cambridge. As advertised in the Boston Globe, the Tsarnaev brothers supposedly wanted to escape the city. If they were in Cambridge, they had a clear route to the highway without ever stepping foot in Allston. However, I didn’t own a car and hadn’t lived near Cambridge in awhile. Maybe there was something obvious I was missing that would become apparent if I was driving it in the moment.

So, last year, Eric and I tried it.

The first thing we agreed upon was that I was right: if both Dzhokhar and Tamerlan were at Collier’s murder scene and wanted to get out of town, there was no need to go to Allston. In fact, there was no need to go to Watertown, either. Together, we hypothesized that there had to be had to be specific reasons to go to both locations.

Then I remembered that in Viskhan Vakhabov’s 302, it was stated that the FBI agent visited him at his residence. In Allston.

And I wondered.

I’ve spent a long time trying to track down Vakhabov’s address. I checked Massachusetts land records – Vakhabov does not seem to own property in the Boston area. I checked licensure records – he got his real estate license in 2010, and in 2017 the license was expired. Right now it is current, until October 4, 2018. But no home address.

In the end, it was frustratingly simple. I checked the White Pages.

I’m not sure this is current; another entry said he lives in Chelsea now, but previously lived in Allston. But another entry listed an Allston address.

Already I recognized the neighborhood. It was right near Packard’s Corner. Quickly, I plugged the address into Google Maps.

Dun Meng was carjacked right around the corner from Viskhan Vakhabov’s apartment.

More on this, and who Tamerlan might have been going to see in Watertown, next time.

Clarification: This article has been updated to include information about other independent researchers writing about Vakhabov. Also, the date listed for Vakhabov’s real estate license expiration is October 4, 2018, not October 8.

Special thanks to Tom Frizzell, Eric Bowsfield, Emily Keller, and others who contributed research to this report.

Works Cited

Cell Phone Evidence:

Chad Fitzgerald’s CAST report

“Jahar Tsarni” Call Log

Tamerlan Tsarnaev’s Call Log

Court Transcripts:

FBI 302 of Viskhan Vakhabov read by Sonya Petri, April 28, 2015

Lobby Conference regarding Viskhan Vakhabov, April 27, 2015

Testimony of Chad Fitzgerald, March 17, 2015

Testimony of Rogerio Franca, April 28, 2015

Publications:

Salky, Steven M. and Paul B. Hynes, Jr. The Privilege of Silence: Fifth Amendment Protections Against Self-Incrimination, 2nd Ed. Chicago, Illinois: American Bar Association, 2014.

That’s an amazingly detailed research. Congratulations.

But as a scholar you should have included or referenced other people’s work, e.g. Jill Vaglica in WhoWhatWhy https://whowhatwhy.org/2015/05/26/boston-bombing-core-mystery-why-are-feds-not-interested-in-this-man/

Hi Margarete,

Thanks very much! As for this article you linked, I don’t recall coming across it when I was first trying to find out information on Vakhabov in 2015, just the Boston.com article I referenced. I think my dad found it in subsequent sweeps, but by that time, there wasn’t any information in it that we hadn’t gleaned on our own.

However, thank you for bringing it to my attention. I do think it is important to note that other independent researchers have had questions about him. Vakhabov also comes up in a chapter about Tamerlan in Amy Knight’s book, Orders to Kill: The Putin Regime and Political Murder. https://www.amazon.com/Orders-Kill-Regime-Political-Murder/dp/1250119340/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1538423604&sr=8-1&keywords=orders+to+kill+amy+knight

However, as in the 2015 articles, by the time we read it, all the information in it was stuff we had already discovered independently. Still, I think it’s a good sign that several separate researchers have come up with the same information – replicability is key!

Some of my research 67 year old Army Vet

https://backpacs.blogspot.com/2018/07/on-subject-of-tsarnaev-backpacks-where.html

Heather, I am holding onto the hope that you will one day conclude, as many others like myself have, that the Boston Marathon bombing was, in fact, a staged false flag courtesy of persons in the U.S. government using prior-amputee crisis actors. Until then, our group will continue to speak out whenever and wherever we see deception and distortion of the narrative, accepting with firm resolve the contempt and disrespect we sometimes encounter. The truth is worth suffering for. Until we are all are on the same page about the bombing, I am glad you are at least still investigating the matter.

Just a friendly reminder that all discussion between readers are to remain civil and respectful. I am removing comments that fall below these standards. Thank you!

I sincerely hope you are not implying my comments are not civil or respectful though we have a difference of belief regarding what really happened in Boston.

No, I was directing it toward the person who replied to you, whose comment I have deleted. Thanks!

Thanks Heather. I pray someday the truth comes out to save Jahar from death and possibly release. Watching and reading all that I do we are living in crazy times. I believe other countries do not like our system of justice and are destroying it.

Thank you for this article Heather.

About the knit cap. You and your readers might be interested in reading trial transcript 1659 : Just prior to the boat view, the defense team asked the presiding judge to point out to the jurors the knit hat that was recovered from the boat. But when he instructed the jurors he did not inform them that a knit hat was indeed recovered in the boat.

About Vakhabov – The Tsarnaev (Tamerlan and his family) were being evicted from their apartment. Originally a 10-year lease was drawn-up at a monthly rate of $800.00. The owner of the building wanted to increase the rent to its street value which was too expensive for the Tsarnaev. That is one reason Tamerlan contacted Vakhabov. Now having said that there might be, as you state in your article, other reasons why Tamerlan contacted Vakhabov. As fo taking the fifth I think it might be because of his drug dealing rather than the bombing. But then ….

One thing that I know for sure is that Dzhokhar who is on death row is INNOCENT, as the government proof suggests. What happen on April 15, 2015 and during that week is no longer important to me as there is so much disinformation out there that it is impossible to make sense of anything.

I personally do not believe that the Tsarnaev brothers nor any friends or ‘associates’ as law enforcement like to qualify them have anything to do with the bombing. However I do believe that a higher force within the US government has everything to do with it and it is called Islamophobia.

Hi Heather,

I just found your blog and have been reading your Thesis avidly. There are so many problems I have with this case, and have from the start. With Jahar again facing the death penalty I feel helpless-I think he was set up. The more I look at this case, the more it makes no sense at all. I believe that 1) There are lots of holes in this story-and a clear violation of Jahar’s rights. Why has Ammnesty International or the ACLU looked into this?